This post was written to support a presentation by the same name—and is a revised version of a post from 2014. In preparation for the talk, I’ve dug pretty deeply into records spanning 1914 to 1919 and found some really good reasons why all Ontario researchers should pay special attention to estate files from this period.

It isn’t difficult to imagine that a war that caused the deaths of some 60,000 young Canadian men and women would affect the plans families had to pass on the goods and property they had accumulated over a lifetime or perhaps several lifetimes. The War years saw fathers or mothers acting as executors for their sons and daughters, and young wives administering their husbands’ estates—decades earlier than they expected. That wasn’t the way things were supposed to happen. It was supposed to be the other way around.

How soldiers’ estates were handled

Members of the Canadian Expeditionary Force were encouraged to write a will before they went into action. It was not a requirement. Some men had made a civilian will before they left home. Many others made use of preprinted forms supplied in England before they were shipped off to France. The wills written by soldiers were collected by the Battalion Paymasters for safekeeping by a special branch of the military set up for the purpose, the Estates Branch. The Paymaster was also to compile a list of the locations of wills for men who had made an earlier will. The list was also submitted to the Estates Branch.

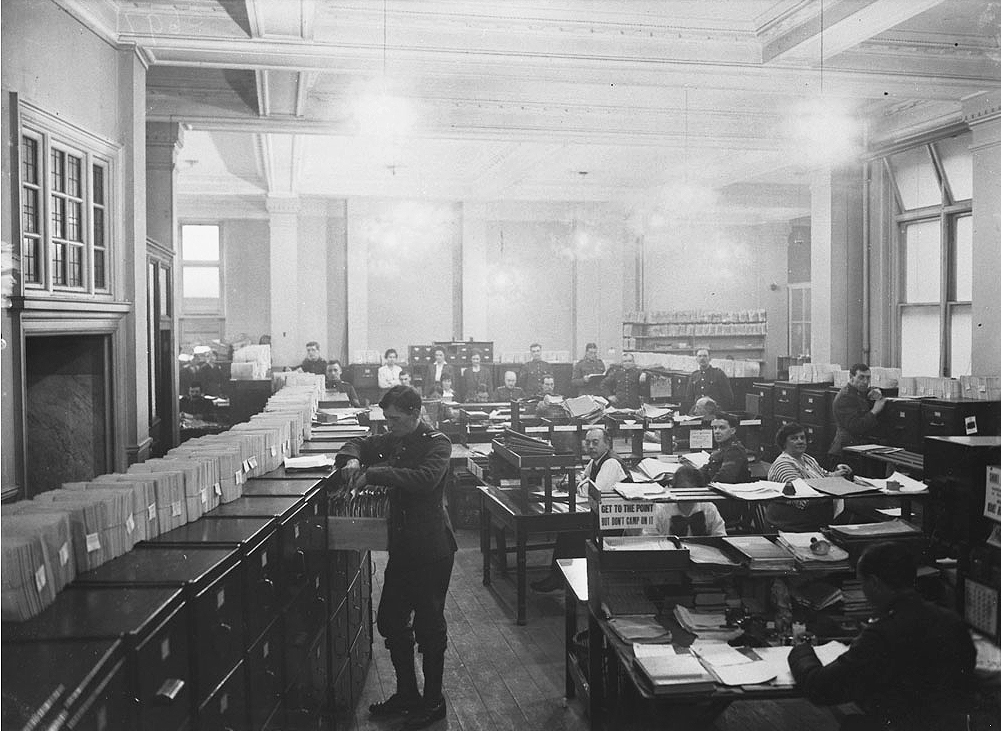

The Estates and Legal Services Branch of the Overseas Military Forces of Canada, operating in London, England, and later in Ottawa, was the depository of some 250,000 soldiers’ wills. When the Estates Branch was notified of a death, they made four copies of the soldier’s will. One copy went to the Canadian Record Office to be added to the soldier’s service file. The original will was sent to the family so it could be probated.

The Estates Branch also oversaw sending the deceased soldier’s effects to his family in Britain or Canada. When a man was killed, an officer was to collect his identity disc and any personal items. The items went to his company’s headquarters, then on to the Battalion Paymaster who sent them to the Estates Branch in London. If the soldier’s family was in Canada, they were passed to the Estates Branch in Ottawa and then on to the family. If the family was in Britain, the Estates Branch distributed the items according to the terms of the will.

Once the soldier’s will was back in the hands of his next of kin in Canada, it could be probated, just like any other will, in the surrogate court where the soldier had lived.[1] To learn more about finding Ontario estate files, consult my book Inheritance in Ontario and/or posts on this site in the Records of Inheritance category. One two-part post, in particular, that deals with the 1914–1919 period is Durham Region Surrogate Courts—Unlocked.

Changes to procedure during this period

Succession Duty Act

The Act had been in effect since 1892, but it was tightened up just before the War in the spring of 1914. The Affidavit of Value and Relationship: is a four-page document that lists the assets and the relatives or other people who will inherit, with their relationships and locations—often with full addresses.

For example, the affidavit[2] for Private Egerton Fernley of Onondaga Twp., listed his foster siblings:

- Christopher William Burrill of Cainsville, Ontario

- Jennie Rebecca Burrill of New York

- Mrs. Annie Down of Smithville, Ontario

- and Violet Edith Beale of Saskatoon (not a sibling)

Enemy Alien Affidavit

The War Measures Act came in to effect in September of 1914. One of its provisions was to stop the flow of money to enemy countries and citizens of those countries. An Order-in-Council by the Ontario government, in December 1915, formalized the process in the surrogate courts. It required that the administrator complete an affidavit saying that the deceased had not been a German, Austro-Hungarian, Turkish, or Bulgarian subject. They also had to explain how they knew that the deceased wasn’t an enemy alien. This affidavit can contain some very interesting genealogical information.

For instance, Mary Ann Forbes of Thessalon says of her late husband who was killed on November 14, 1917, in action with the 12th Canadian Machine Gun Company:

“That I know the father of the late Robert Spence Forbes, and knew his mother before her decease. That they are of Scotch descent and I am informed and believe that my late husband was born in Scotland and was, therefore a British Subject.”[3]

In another example, Paolo Cuischini of Sault Ste Marie, explains how he knows that his friend Gaspari Donati, who died in 1916 on active service with the Italian army, was not an enemy alien:

“That I knew both the father and mother of the deceased and they were both Italian subjects. My home was about a mile and a half from theirs in the municipality of Mondolfo, Province of Pesaro, Italy. The said deceased was also an Italian subject.”[4]

Special provisions for soldiers

Through the War years there were a number of allowances and exceptions for men and women on active service written in to the legislation. One of the most interesting allowed for letters to be admitted as wills. The actual letters will be included in the estate file.

Private William Wauchope of Toronto, who was killed on April 24, 1915, wrote to his siblings just three months before on January 26, 1915:[5]

“Just a short note in reply to your welcome letters, one yesterday, one today, very glad to hear from you. You all appear to be worrying more about my money than I am myself… If I don’t come back I trust you will all agree to divide whatever is to my account between Charlie, Jack and you while Martha has the lots, so the longer the Germans let me live, the more you will have to get.”

If you had ancestors who died in Ontario during the War years, be sure you’ve looked for their estate files. They will provide more insight into how the turmoil impacted on your family, as well as (with a little luck) some unexpected treasures.

Notes

[1] The preprinted military wills form neglected to ask for an executor, so the courts could not grant Letters Probate. The soldier’s wishes were acknowledged, though, with a grant of Letters of Administration with Will Attached. (The additional paperwork required for administration is a bonus for historians.)

[2] Estate file of Egerton Fernley, 1917, #4647, RG 22-325 Brant Co. Surrogate Court, film MS 887-116, Archives of Ontario

[3] Estate file of Robert Spencer Forbes, 1918, #1231, RG 22-360 Algoma District Surrogate Court, film MS 887-27, Archives of Ontario

9 thoughts on “Inheritance Interrupted: Estate files during WWI”

Very interesting and a silver lining, I guess, for people that lost relations in the war. Unfortunately/fortunately I don’t have any close relations lost that way.

Thanks, Donna. Glad you found it interesting. Don’t forget that the “silver lining” applied to every estate file, not just for men and women on active service.

Very informative blog. I do stress that Wars always have a huge impact on family history and genealogical research. Though they are often sources of major brick walls due to the dislocation of families, they are also sources of new documents created because of the conflict. Not quite a silver lining, but certainly something to consider for every conflict. What documents were created because of the War that can be used to find out more information on a family.

Thank you again.

Very interesting. Robert Spence Forbes was my great uncle and I was just through Thessalon to look at the war memorial with his name on it.

I’m glad you found the post, Ian. Thanks for letting me know.

I found your presentation to OGS Durham Region Branch last evening very fascinating! I have just found a Form of Will in the WW I file of Lemuel Oscar Bunt. He later went on to become a Methodist/United Church minister and died in 1978!

Are you familiar with the book Acta Victoriana, which is a record of all graduates and undergraduates of Victoria College who served in WW I. There are about 705 names and most with photos. I donated my father’s copy to the Mayholme Foundation in St. Catharines, but before I did, I indexed it and kept a digital copy. I would be happy to share it with anyone who wishes. Harold Staples Brewster is one of the first in it.

Thank you, Bob. Kind of exciting to hear from someone who attended the meeting via the livestream!

Enemy alien affidavit. If someone WAS an enemy alien (e.g. Ukrainian), what would happen to property? I have a couple of these affidavit records, but just wondered what would have happened to property if one were of one of the enemy alien descents. In my case, NOT military case, but a death because of Spanish flu.

Hi Heather. The War Measures Act prevented funds going to “enemy aliens” during the war without special dispensation. With permission of the Solicitor of the Treasury, moderate sums could be paid out to beneficiaries resident in Canada. It sounds like cases were considered individually. You can read more about the regulations here: https://archive.org/details/surrogatecourtru00ontauoft/page/92/mode/1up

Jane